- The Bank of International Settlements has published a chapter from its Annual Economic Report detailing a unified ledger as the future of monetary systems.

- The proposed ledger diverges from blockchain fundamentals and significantly lacks user autonomy, transparency, and decentralization.

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) recently published the third chapter of its upcoming Annual Economic Report. Entitled Blueprint for the Future Monetary System: Improving the Old, Enabling the New, this chapter outlines the BIS’ vision to create a “unified ledger” to serve as the future of the monetary system and how the tokenization of assets will enable this.

This publication emphasizes how out of touch the BIS is. They spell tokenization wrong throughout the chapter and describe a blockchain void of all the aspects that make distributed ledger technology beneficial for users. This proposed unified ledger is a pure centralized system.

Crypto Bad, BIS Good

Right away, the chapter undermines cryptocurrency as demonstrated through the following excerpt:

“Crypto and decentralised finance (DeFi) have offered a glimpse of tokenisation’s promise, but crypto is a flawed system that cannot take on the mantle of the future of money.2 Not only is crypto self-referential, with little contact with the real world, it also lacks the anchor of the trust in money provided by the central bank.”

People turn to cryptocurrency because it is trustless. The “anchor of trust” in central banks is the very reason driving people away from the current monetary system. Practices like fractional reserve lending, high transaction fees, single points of failure, and intermediary bureaucracy are why users value being the sole custodians of their financial assets, a reality that crypto offers.

Tokenization

Despite misspelling the concept, the chapter is correct in its explanation of what tokenization is. The BIS holds that third-party account managers maintain accurate ownership records within traditional ledger systems. In contrast, in a tokenized ledger, transaction records essentially maintain themselves as assets are transformed into “executable objects” expressed through programmable smart contracts (the chapter consistently recognizes smart contracts but never mentions blockchain).

This assessment is correct so far, but the BIS claims that while tokenization does not eliminate the role of intermediaries or third-party account managers, it fundamentally changes their nature, something that the BIS portrays as unfavorable.

The chapter further explains that in a tokenized ledger, users assume a trusted intermediary role, responsible for their own transactions rather than a bookkeeper recording individual transactions for account holders. Assets exchanged within a tokenized ledger system have a digital unit of value attached to them called a token.

Tokens function much deeper than just digital entries in a database; they combine the records of the underlying assets typically found in traditional databases with the rules and logic governing the asset transfer process. This allows tokens to be programmed to meet specific user or regulatory requirements for individual assets, unlike TradFi banking systems, where the rules for updating asset ownership are standardized.

The BIS claims that tokenization introduces two key elements:

- It eliminates the need for messaging standards to transfer assets, and it also eliminates intermediary account managers to maintain ledger records, enabling a high degree of composability.

- It empowers the execution of actions based on conditions through smart contracts, which are logical statements such as “if, then, or else.”

Unified Ledger Architecture

The BIS holds that for its unified ledger to operate efficiently, it must combine all the components needed to complete a transaction on one platform and feature assets as executable objects which can be transferred safely and securely.

Assets must be able to be transferred without going through external authentication and verification processes and without relying on external messaging systems. Congratulations to the BIS for describing a system that already exists (it’s the blockchain).

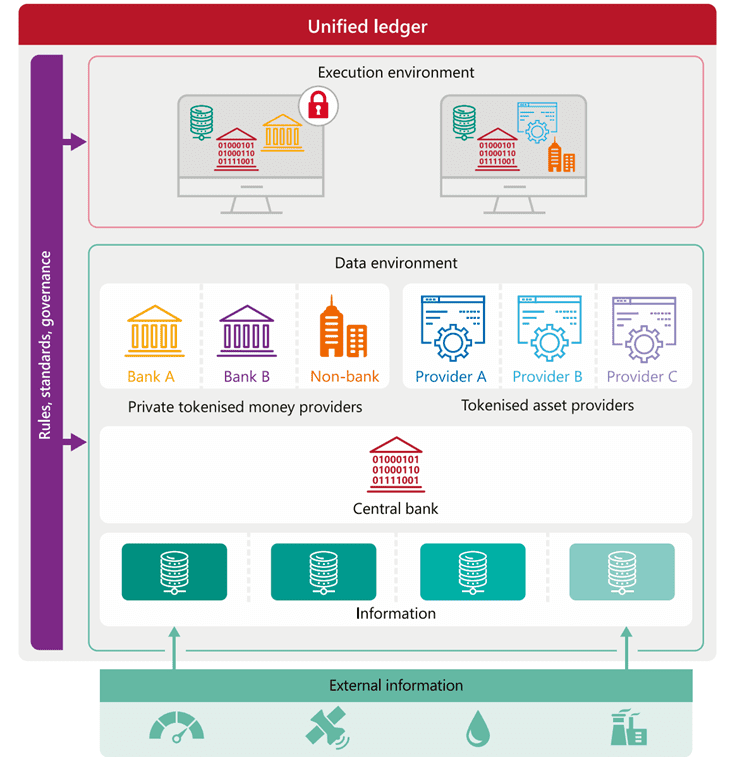

The unified ledger would comprise a data and execution environment with a governance system to dictate environment functions.

The data environment will contain monies, assets, and information (internal or external to the ledger), all partitioned to delineate ownership and access. Operations involving one or more of these elements will be carried out in the execution environment, either directly by users or through smart contracts.

The above infographic is very similar to a breakdown of blockchain layers (hardware layer, data layer, network layer, consensus layer, and application layer) which function to reach consensus, execute and settle user transactions, and provide data availability.

Governance of the BIS unified ledger—and this is where the chapter drastically diverges from blockchain—would be handled by central banks and regulated private participants. For example, when money and payments are exchanged on the ledger, a central bank will be responsible for providing transaction settlement. In a blockchain network, this is handled by the consensus mechanism, a unilaterally accepted protocol that operates completely decentralized.

The BIS contradicts itself when describing ledger governance as it holds that governance arrangements could take various forms, much like traditional payment systems, where public ownership, regulation and oversight, and private mutual ownership are all viable options. However, regulated and supervised private participants should remain in charge of customer-facing activities to ensure integrity.

So how are all the aforementioned activities viable if a single authority dictates customer operation? Perhaps they’re only feasible conditionally, as the chapter conveniently doesn’t specify.

The most concerning makeup of the BIS’ unified ledger is its complete lack of transparency. In a blockchain, once finality is reached, block data is immutable and ordered chronologically; it cannot be altered or erased and is publicly viewable by the entirety of the network. The chapter describes that a critical element to guaranteeing privacy is to create partitions in the ledger’s data environment.

Each entity, such as banks or the owners of tokenized assets, will see only transactions and associated data on their partitions. The account owners update the data environment using their private keys. These private keys will authenticate and authorize transactions, ensuring legitimate account owners can change their own partition of the ledger’s data environment. In a blockchain, sharding exists to increase scalability by disaggregating network components into smaller subsets of function or data availability, called shards.

The difference between the unified ledger partitions and blockchain shards is that within the blockchain, shards are timestamped to be still viewed as a concurrent part of the ledger, and the data that shards contain is still accessible to the entire network so that accountability can be upheld. Data within unified ledger partitions will not be viewable to the whole network, allowing private actors to do what they please as the only entity to hold them accountable would be a central authority, i.e., a single point of failure.

Conclusion

The BIS’ proposed unified ledger is Byzantine fault intolerant due to the authorities that would govern it, opaque because of its partitions, and utterly centralized.

This chapter demonstrates the BIS’ lack of understanding by consistently misspelling tokenization and failing to acknowledge the role of blockchain technology in the current landscape. It undermines cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance (DeFi) as flawed systems without the trust provided by central banks, even though the attraction of cryptocurrencies lies precisely in their trustless nature, as users value autonomy and control over their financial assets.